Is the “Far-Right” the New Centre-Right?

The perception that individuals who once identified as center-right are now branded as “far right” can be attributed to several factors. These factors include shifts in political norms, changes in societal values, the influence of media, and the evolving definitions of political ideologies.

Shifts in Political Norms

Over time, political norms and the policies associated with different parts of the spectrum can change. For instance, positions on immigration, national identity, and economic policy that were mainstream for center-right parties a few decades ago might now be seen as more extreme due to the overall shift in societal attitudes. If the general political climate has moved leftward, views that were once considered center-right might now appear more radical by comparison.

Changes in Societal Values

Societal values evolve, influenced by cultural, economic, and technological changes. Progressive movements advocating for social justice, equality, and environmental sustainability have gained prominence, pushing many societies toward more liberal positions on various issues. This evolution can make previously moderate conservative positions appear more rigid or extreme.

Influence of Media

Media plays a crucial role in shaping public perception. Sensationalist coverage, polarization in news reporting, and the amplification of extreme viewpoints on social media can distort the perception of political ideologies. Media outlets might label individuals or groups as “far right” for engaging in rhetoric or actions that deviate from the current mainstream narrative, regardless of whether their positions have fundamentally changed.

Evolving Definitions of Political Ideologies

Political labels such as “far right,” “center-right,” or “left” are not static and can vary significantly depending on context and geography. What is considered far right in one country might be seen as center-right in another. As the political landscape changes, so do these definitions. This fluidity can lead to confusion and rebranding of individuals or groups based on contemporary standards.

Reaction to Polarization

The political landscape has become increasingly polarized, especially in many Western democracies. As political discourse becomes more polarized, the center itself may shift, pushing moderate positions toward one extreme or the other. In a highly polarized environment, individuals and policies are more likely to be categorized in binary terms, leading to oversimplification and mischaracterization.

Impact of Populist Movements

Populist* movements, which often emphasize nationalism, anti-immigration policies, and scepticism of global institutions, have gained traction in recent years. These movements have contributed to the redefinition of the political right, with mainstream conservative parties sometimes adopting more populist rhetoric to maintain electoral support. This shift can cause traditional centre-right positions to be associated with far-right ideologies.

Perception and Identity Politics

Identity politics and cultural issues have become central to political debates. As societies grapple with issues like race, gender, and identity, positions on these topics can quickly become polarized. What was once a moderate stance on cultural issues might now be seen as far-right due to the heightened sensitivity and changing norms around these discussions.

In conclusion, the rebranding of centre-right individuals as “far right” is a complex phenomenon influenced by shifting political norms, evolving societal values, media influence, changing definitions of political ideologies, polarization, populist movements, and the prominence of identity politics. Understanding these dynamics is essential for a nuanced perspective on contemporary political discourse.

*Popularism – It’s not a dirty word!

…and we can all be Popularists.

The term “populism” generally refers to political approaches that strive to represent the interests and voices of the general population, often pitting “ordinary people” against a perceived elite or establishment. While it does involve appealing to popular public opinion, it carries a broader and more nuanced connotation. Here are the key aspects of populism:

Core Characteristics of Populism

- Anti-Elitism: Populists often frame their politics in opposition to the elites or the establishment, portraying these groups as corrupt or out of touch with the needs and desires of the common people.

- Appeal to the “Common People”: Populists claim to represent the voice and interests of the average person, often invoking a sense of unity among “the people” against “the elite.”

- Simplification of Complex Issues: Populist leaders often present complex political, economic, or social issues in simple, straightforward terms, which can be appealing to the general public but sometimes glosses over the intricacies of policy-making.

- Charismatic Leadership: Many populist movements are led by charismatic leaders who are able to connect with the public on a personal level, often through emotional and direct communication.

- Nationalism and Sovereignty: Populist movements frequently emphasize national sovereignty and can adopt nationalist rhetoric, prioritizing the interests of the nation-state over global or international considerations.

Populism vs. Popularity

While populism involves appealing to popular opinion, it is distinct from simply being popular or responding to public opinion in a straightforward manner. Here’s how:

- Ideological Component: Populism often involves a clear ideological stance that is critical of the establishment and seeks to radically change the status quo, whereas popularity can be achieved without necessarily challenging the existing system.

- Us vs. Them: Populism typically frames politics as a struggle between the “righteous people” and the “corrupt elite,” whereas being popular doesn’t inherently involve this dichotomy.

- Mobilization and Rhetoric: Populist leaders and movements actively mobilize their base with a specific rhetorical style that emphasizes direct, often polarizing, communication. Popular politicians might use similar tactics, but not necessarily with the same populist framing.

Examples

- Left-Wing Populism: Movements like those led by Bernie Sanders in the United States, Podemos in Spain or Jeremy Corbyn in the UK emphasize economic equality, social justice, and criticism of corporate power, framing their message around the needs of the many versus the power of the few.

- Right-Wing Populism: Movements like those led by Donald Trump in the United States, Marine Le Pen in France or Nigel Farage in the UK emphasize nationalism, anti-immigration policies, and scepticism of globalism, often framing their message around protecting the nation from external and internal threats posed by elites and immigrants.

- Centre-Right Populism: Boris Johnson can be seen as a center-right politician who adopts populist strategies and rhetoric when it suits his political objectives. His blend of traditional conservative policies with populist elements, particularly during the Brexit campaign and his tenure as Prime Minister, demonstrates his ability to appeal to both mainstream conservative voters and those with more populist inclinations.

In summary, while populism does involve appealing to public opinion, it is characterized by its oppositional stance against the elite, its ideological framework, and its specific rhetorical and mobilization strategies. It is more than just popularity; it is a distinct approach to political engagement and leadership.

What Others Have Said

The “right-wing” agenda today is just the centrist agenda of 20 years ago. The left has become an extinctionist movement.

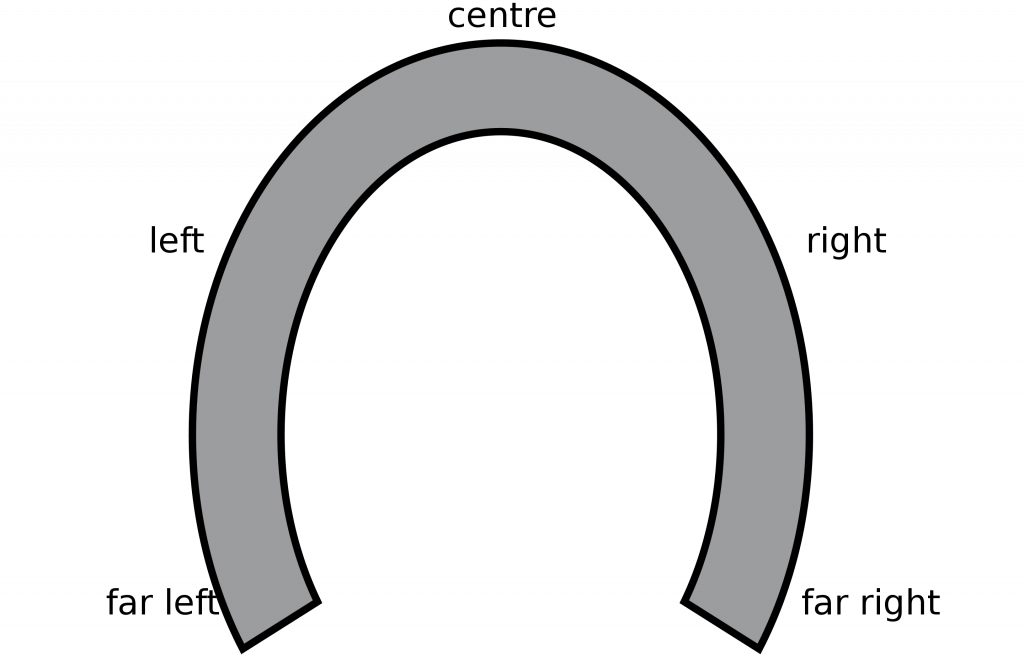

In popular discourse, the horseshoe theory asserts that advocates of the far-left and the far-right, rather than being at opposite and opposing ends of a linear continuum of the political spectrum, closely resemble each other, analogous to the way that the opposite ends of a horseshoe are close together. The theory is attributed to the French philosopher and writer of fiction and poetry Jean-Pierre Faye in his 2002 book Le Siècle des idéologies (“The Century of Ideologies”).

Wikipedia.